Video Navigation in React

Seeking to a time in a video of a sibling component

Declarative data design

I recently started learning React. It’s a framework that solves a lot of problems in front-end web development. But this post is not a React tutorial. There are plenty of those that are extremely well written. Instead, I want to focus on understanding React’s “declarative” data philosophy. This strongly opinionated design constraint is a key to React’s success, and yet as a new React developer it can seem to get in your way a lot. So let’s spend a section diving into the idea.

In short: At a given time, the entire application has a given “state”, representing all data including user-inputted text, switches turned on or off, data fetched asynchronously from back-end or external servers, etc. A component – this could be a simple line of text or a complex form with images and other widgets – with a given state should always look the same. This transformation of state to HTML is precisely what the render() function does.

The alternative, “imperative”, data philosophy, has a web app begin with certain HTML (DOM) elements, and will often use javascript to react to events (such as typing, clicking, fetching remote data) to cause changes to those elements. It is quite common to, erm, “react” to events like these by directly updating the DOM without storing that information in your javascript objects. The state of your application in this way is then, in part, stored in the DOM itself.

When using imperative design, it can be quite easy to get your application state out of sync with what’s actually going on in the DOM. Going declarative, the state dictates the components, and thus it can be near impossible (in ideal conditions) to get out of sync. A common example I see regularly is when a password field triggers the “login” button to become enabled. Using a password manager, the trigger is missed, the login button remains disabled, and I can’t log in without typing and deleting a dummy character in the field.

So declarative data design seems great! But let’s go through an example where it just doesn’t seem to fit.

Declarative data for video

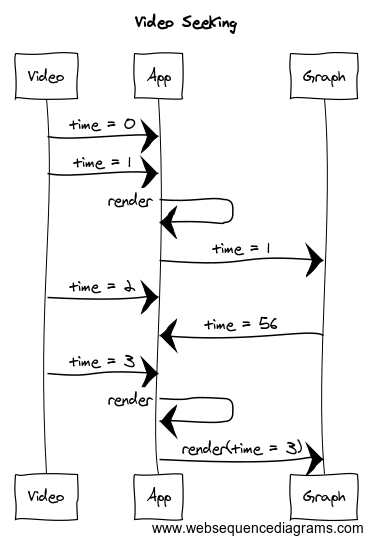

Let’s imagine an app with a video components and an analytics graphs that tracks the playtime it the video. I’m going to talk about data flow from the video to the graph and in the other direction. Let’s start with the simple case first: updating the graph in response to the video.

This simple case

In an imperative design, we might broadcast the current time from the video component directly to the graph component to cause it to update. But in React, a component renders according to its current state, and state information only flows down. Well, that last part can’t be quite true, because the video is damn well going to manage its own playhead state. Exceptions to the rule like this are common when dealing with more complex elements that we have no control over, and that’s ok. What we’ll do is trigger a callback on update of the video time and store the current time in the parent element as the application’s state. This will be out of sync with the video’s true time by tens to hundreds of milliseconds but it will still be a pretty reasonable approximation of a “ground truth” state.

Then, simply, the graph component is passed this “approximate ground truth” state from the common parent, and renders accordingly.

class App extends React.Component {

render() {

return (

<VideoDisplay

onTimeUpdate={time => this.setState({time: time})}

/>

<Graph time={this.state.time} />

)

}

}

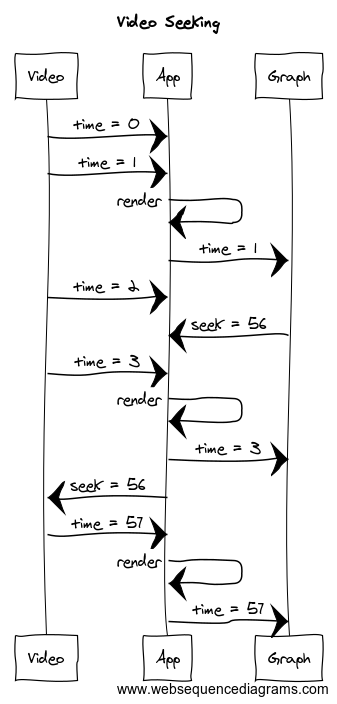

The more difficult case

Now let’s discuss data flow in the reverse direction. Let’s allow the user to click on the graph in order to navigate to the corresponding time in the video. Cool feature, right? Well we can’t simply update the same time variable in the parent’s state. This is getting repeatedly clobbered by updates from the video, and the video element may never get a chance to respond to the seek information.

Ok, so “time” represents the time as reported by the video. Let’s use different variable, and call it “seek”. We’ll pass the message up to the parent to update “seek”, and it’s ok if we get five more “time” updates in the meantime. React soon figures out that seek has new value, and can pass that information down to the video component.

But we have our first problem. Unlike most state information, seek is inherently transient. The video component manages its own time / state! We don’t want to re-render the video element nor reload the video source onto the page. No, seek is inherently transient, and the only way to use it is to issue the imperative: video.currentTime = seek.

We can issue this command in a lifecycle hook of the React component, which fires when the <VideoDisplay> component receives a props update.

class App extends React.Component {

render() {

return (

<VideoDisplay

seek={this.state.seek}

onTimeUpdate={time => this.setState({time: time})}

/>

<Graph

time={this.state.time}

onSeek={time => this.setState({seek: time})}

/>

)

}

}

class VideoDisplay extends React.Component {

componentWillUpdate() {

if (this.props.seek) {

this.videoElement.currentTime = this.props.seek;

}

}

}

And now we have our second problem. Because React makes us think this way, seek is a persisted state instead of an imperative event. So the video will henceforth repeatedly seek to the desired time, which is very much not desired. The action of seeking a video is inherently a one-time thing. It is inherently imperative. React doesn’t like imperative.

How do we get around this? One way is to define seekId as well. The <VideoDisplay> component will remember this seekId, and only respond if a new seekId comes in.

class VideoDisplay extends React.Component {

componentWillUpdate() {

// Only respond to seek if there's a new seekId

if (this.props.seekId > this.state.seekId && this.props.seek) {

// Save the seekId so we don't keep repeating it

this.setState(seekId: this.props.seekId);

// Perform seek.

this.videoElement.currentTime = this.props.seek;

}

}

}

To me, this is starting to code-smell just a little. Not just for the added bookkeeping, but for the way we’re explicitly ignoring these props most of the time. We’re forcing a transient, imperative command into a persistent state construct, and the hackiness shows. My best explanation about this code smell is simply that seek and seekId are not “properties” of the VideoDisplay component. Calling them so is informationally incorrect and seems to be abusing the construct.

So can we reframe our actions using constructs that fit more naturally with React’s concept of state? What if we think about this seek command as an object that represents a message to be consumed. This could easily be extended to commands other than “seeK”, but we’ll stick to seeking for this post. Essentially, we are modeling this transaction as placing a command on a queue and popping it off when consumed.

class App extends React.Component {

// Remove the command once consumed

onSeekConsumed(time) {

// Remove if the current seek command matches the one consumed

if (time === this.state.seek) {

this.setState(seek: null);

}

}

render() {

return (

<VideoDisplay

seek={this.state.seek}

onTimeUpdate={time => this.setState({time: time})}

onSeekConsumed={time => this.handleSeekConsumed(time)}

/>

<Graph

time={this.state.time}

onSeekRequested={time => this.setState({seek: time})}

/>

)

}

}

class VideoDisplay extends React.Component {

componentWillUpdate() {

if (this.props.seek) {

this.videoElement.currentTime = this.props.seek;

// We could also call this asynchronously once we've confirmed

// that the video actually did seek.

this.onSeekConsumed(this.props.seek);

}

}

}

This is, of course, even more overhead, and yet somehow I like it better. Both solutions are more cumbersome than the event-drive methods of ye-olde-javascriptte. If you really wanted to, I guess you could always cheat by passing a function from the <VideoDisplay> component up to the parent so the parent can, imperatively, call the seek function directly:

class App extends React.Component {

render() {

return (

<VideoDisplay

exposeSeekFunction={fn => this.setState({seekFunction: fn})}

/>

<Graph

onSeekRequested = {time => this.state.seekFunction(time)}

/>

)

}

}

class VideoDisplay extends React.Component {

componentDidMount() {

seekFunction = (time => { this.videoElement.currentTime = time });

this.props.exposeSeekFunction(seekFunction);

}

}

Bad developer. Bad.

What do you think? Is there a better way to frame this behavior that fits better within React’s constructs? Let me know in the comments!