Hacking FactoryBot to build a factory UI (1 of 2)

Part 1: The main guts of the FactoryBurgers gem

Motivation

As stated in the last last post, our goal package up a front end interface for FactoryBot and distribute the functionality as a Ruby Gem. In the last post we built the gem, leaving the details of the FactoryBot ~hacks~ hooks as a black box. Today we open that box. We’ll find a fair amount of guessing and hackery in order to do what we want to with FactoryBot. It’s gonna be fun!

Quick Recap

When we left off, we had just built a gem that could be installed in a Rails app to provide a UI to FactoryBot simply by using

mount FactoryBurgers::App, at: "/factory_burgers", as: "factory_burgers"

A user could then go to localhost:3000/factory_burgers (for a standard rails s startup) to view and use the UI. We didn’t go over what the UI looked like or how the back end works. This post will focus on the back end, but let’s start from the UI to make things easier to follow from the user perspective.

A Sneak Peek at the UI

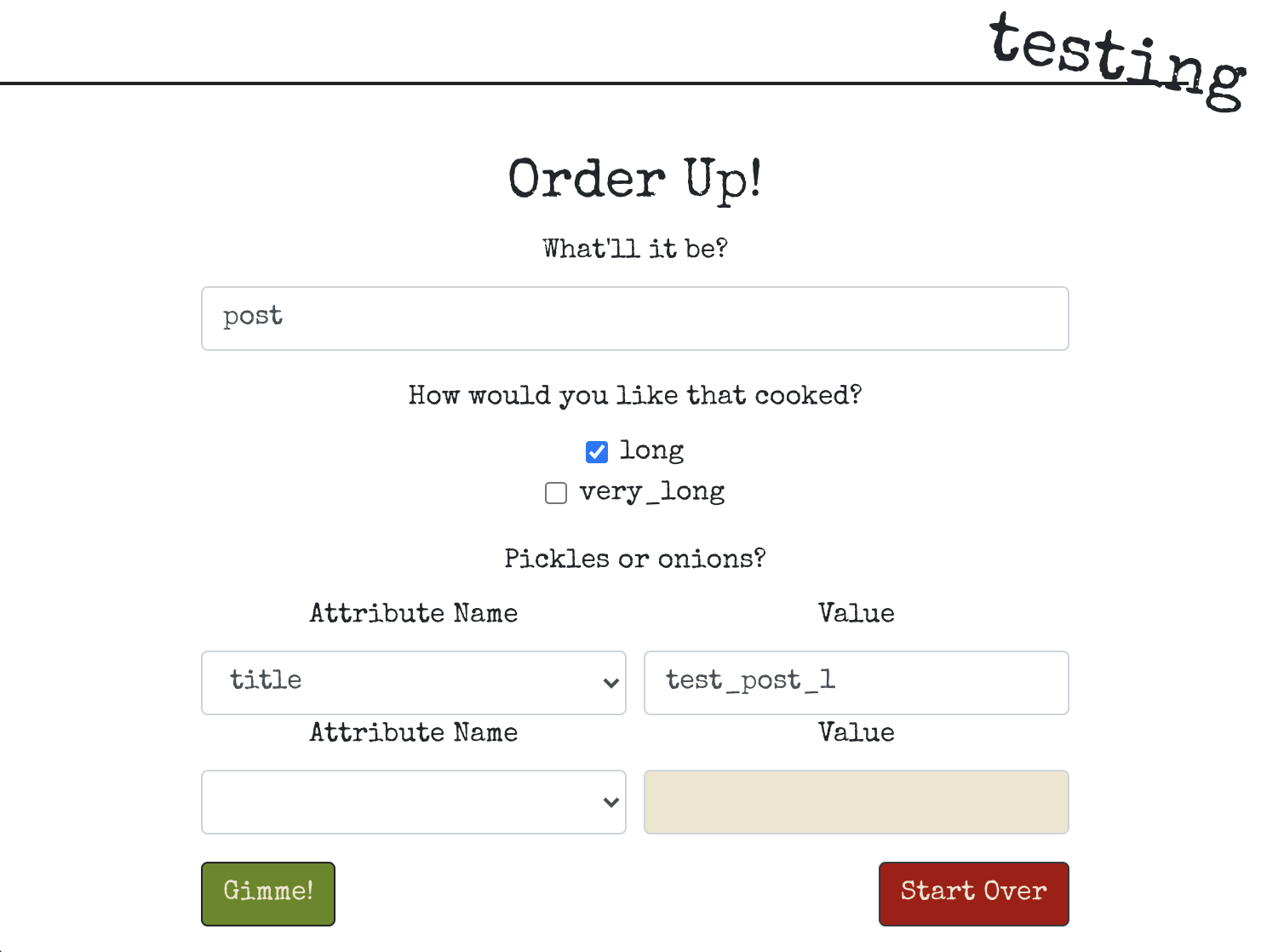

When a user navigates to /factory_burgers, they’ll be greeted with a form:

This form allows the user to select from a list of FactoryBot factories to create an object. Once selected, the form dynamically creates checkboxes for each registered trait as well as model attributes.

The selections above are the UI equivalent of writing

FactoryBot.create :post, :long, title: "test_post_1"

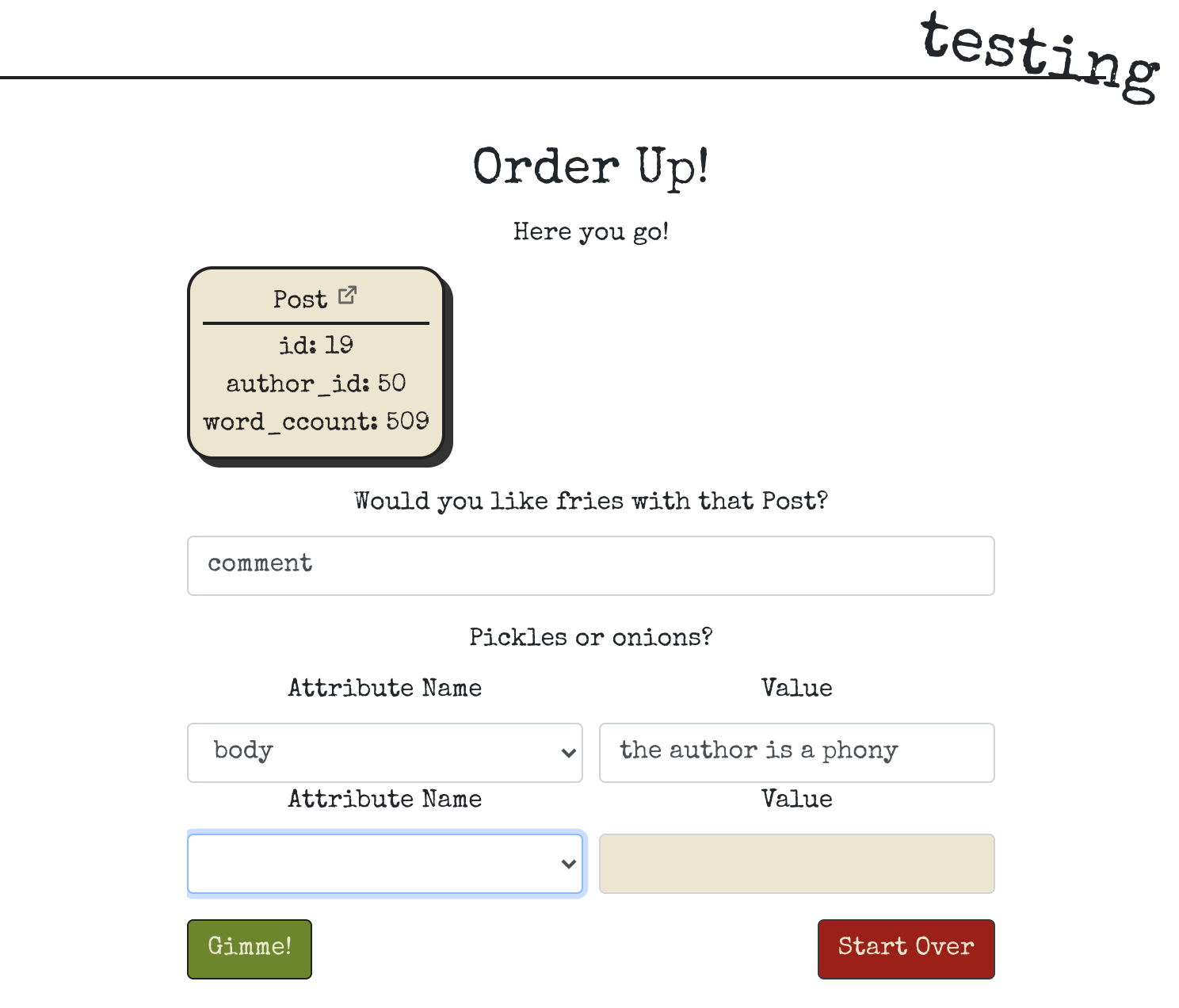

Once the user hits “Gimme”, the object is created and displayed. But we’re not done! Now we go deeper. Using ActiveRecord introspection, we find the associations defined on the model (here, Post), then find the factories that are capable of building any of those associations, and allow the user to build out associated objects to the Post instance we just created.

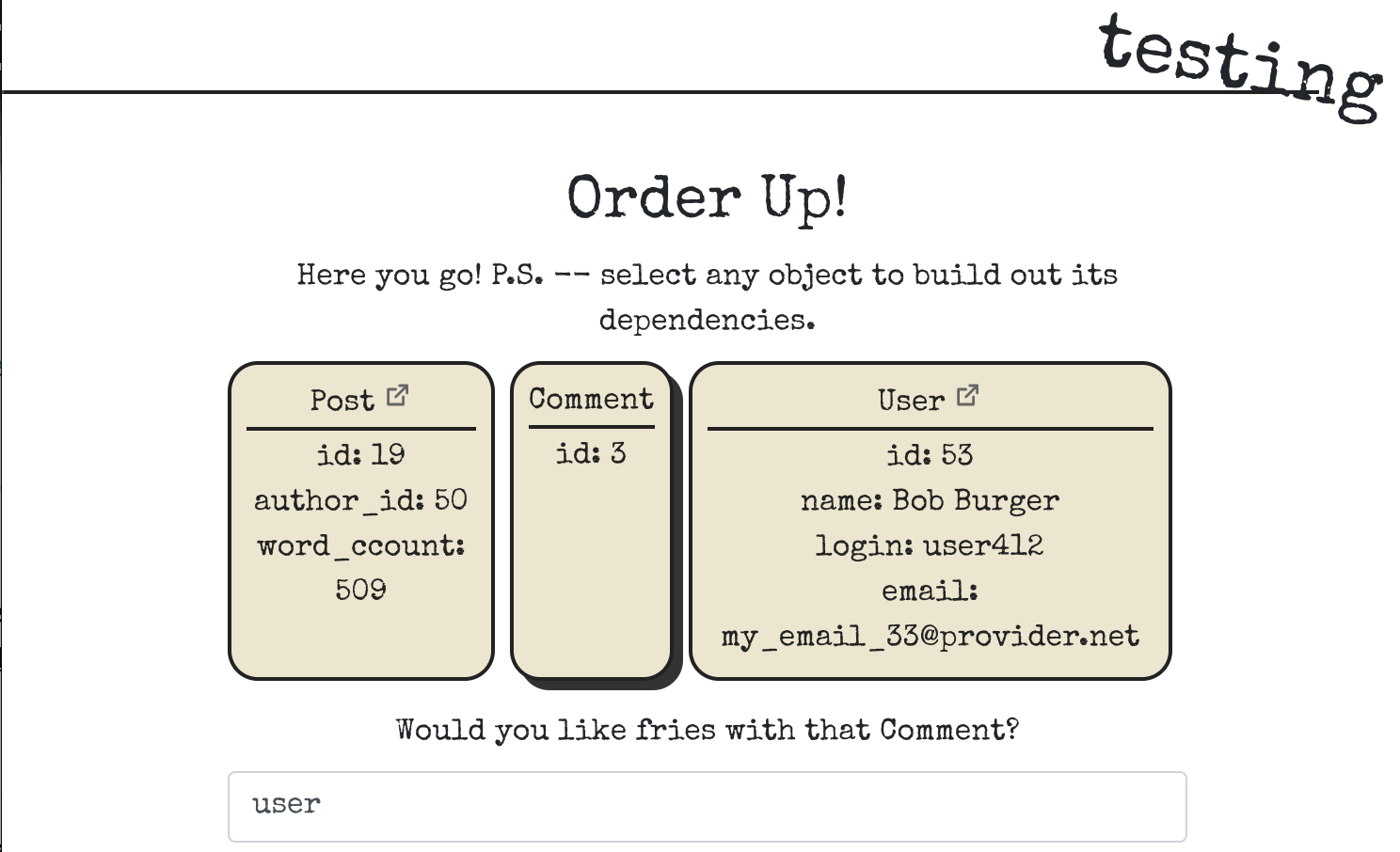

As the user builds out additional objects, they can select and of the objects already ordered to build out additional associations. When we’re all done, we can have a look at everything we’ve done.

So now that you have the User Journey, we’ll spend the rest of this post going over

- How to use these factories in a non-test environment

- How to list all of the factories

- How to discover and expose traits, attributes, associations, and factories for these associations

- How to get around some issues when using FactoryBot outside a immediate tear-down test db environment (cough uniqueness validations cough).

- How to allow customization of the display such as you see above: different models display different summary attributes and can even have links to your application’s show pages for these resources.

We won’t cover the UI (React with very cool animations, thank you very much) or the controllers / middleware that connects the two. Most of the latter was covered in the last post. If you’re looking for more context that is in this post, check out the full codebase.

The Back End

Prerequisites

The first prerequisite is to make sure you have FactoryBot enabled in your development environment. So make sure factory_bot is in your Gemfile and included in at least the :development (or equivalent) group and not just :test.

Next, we need to load the registered factories; we don’t get this for free. But in Factory Bot 6.x, we can do this as easily as

def load_factories

FactoryBot.reload

end

We’ll call this from an initialization script, init.rb

require Pathname(__dir__).join("factory_bot_adapter.rb")

begin

require "factory_bot"

rescue LoadError

raise LoadError, "Could not load factory_bot. Please make sure it is installed."

end

FactoryBurgers::FactoryBotAdapter.load_factories

Loose coupling

A lot of data and methods we’re going to deal with will be specific to the version of FactoryBot in use. For example, in FactoryBot 4.0, FactoryBot.factories will give you a list of FactoryBot::Factory object. In 6.0, you would use FactoryBot::Internal.factories. In order to keep our middleware and view well oganized and robust, we’ll abstract all of those relevant details into adapter classes. For this post, many of the floating methods you see defined end up living in FactoryBurger::FactoryBotAdapter::FactoryBotV6, which is the 6.x-specific adapter. This way, we can define entry point methods such as FactoryBurgers.factories without worrying about the version, effectively decoupling the consumer of our back-end code (the middleware) from the specific library and version powering the back-end.

Listing Factories

Once we have the above, getting a list of factories using FactoryBot 6 is simply

def factories

FactoryBot::Internal.factories

end

The return value is an Array of FactoryBot::Factory objects. We’ll wrap that in our own data class for stability. For our purposes, that means providing access to the factory name, model attributes, and factory traits.

module FactoryBurgers

module Models

class Factory

attr_reader :factory

def initialize(factory)

@factory = factory

end

def to_h

{

name: name,

class_name: class_name,

traits: traits.map(&:to_h),

attributes: attributes.map(&:to_h),

}

end

def to_json(*opts, &blk)

to_h.to_json(*opts, &blk)

end

def name

factory.name.to_s

end

def class_name

build_class.base_class.name

end

def traits

defined_traits.map { |trait| Trait.new(trait) }

end

def attributes

settable_columns.map { |col| Attribute.new(col) }

end

private

def build_class

factory.build_class

end

def settable_columns

factory.build_class.columns.reject { |col| col.name == build_class.primary_key }

end

def defined_traits

factory.definition.defined_traits

end

end

end

end

We’ll do the same for traits and attributes. For attributes, we used factory.build_class to get the ActiveRecord class, then called columns to get its list of columns. Finally, we reject the primary key, since we don’t want to allow the user to specify that in the UI. The data class is define as follows:

module FactoryBurgers

module Models

class Attribute

attr_reader :column

def initialize(column)

@column = column

end

def to_h

{name: name}

end

def to_json(*opts, &blk)

to_h.to_json(*opts, &blk)

end

def name

column.name

end

end

end

end

To get traits for a factory, we used factory.definition.defined_traits, where factory is a FactoryBot::Factory, and the return value is an array of FactoryBot::Traits. Our data class:

module FactoryBurgers

module Models

class Trait

attr_reader :trait

def initialize(trait)

@trait = trait

end

def to_h

{name: name}

end

def to_json(*opts, &blk)

to_h.to_json(*opts, &blk)

end

def name

trait.name

end

end

end

end

Both of these are very basic classes whose single responsibility is to encapsulate factory, trait, and attribute information in a manner our middleware can reliably consume. Here’s an example.

factory = FactoryBurgers::Introspection.factories.find { |f| f.name == :post }

pp FactoryBurgers::Models::Factory.new(factory).to_h

{:name=>"post",

:class_name=>"Post",

:traits=>[{:name=>"long"}, {:name=>"very_long"}],

:attributes=>

[{:name=>"created_at"},

{:name=>"updated_at"},

{:name=>"author_id"},

{:name=>"title"},

{:name=>"body"}]}

You can see how each of the items in this data structure map to the form inputs in the screenshots above.

When the form gets submitted, we use the factory, traits, and attribute data to build the object using FactoryBurgers::Builder#build:

def build(factory, traits, attributes)

FactoryBot.create(factory, *traits, attributes)

end

This simply maps the data we parse and pass from the middleware to the create call you’re likely already familiar with. If you’re used to seeing create called without an explicit reference to FactoryBot, that’s because you have some setup (such as spec_helper.rb in rspec) that defines these methods in your test’s execution context. We don’t have and don’t wan’t that, so we’ll just call the method on FactoryBot explicitly.

Customization

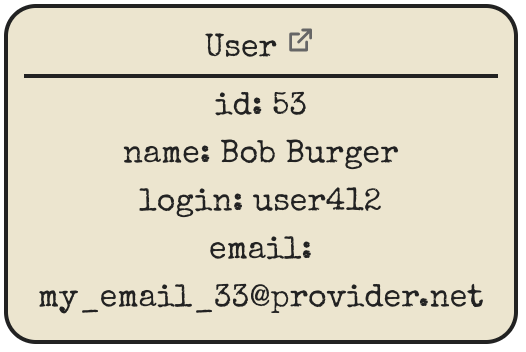

The next cool feature we’ll build into the gem is the ability to customize what information we display for each built object. Notice how our “User” object UI above had a number of useful attributes on display, but “Comment” had only the id. We don’t want to overwhelm the user with all attributes of a given object, but we do want to provide any information the developer deems useful.

Our strategy will be to use customizeable presenters. We’ll construct a presenter base class that application developers can subclass, exactly as Rails provides the base class ActiveRecord::Base that can be subclassed. We’ll allow application developers to define their presenters using one of two forms:

-

Create a class and reference it explicitly

FactoryBurgers::Presenters.present "User", with: FactoryBurgers::Presenters::UserPresenter -

Use an anonymous presenter defined inline

FactoryBurgers::Presenters.present("Post") do attributes do |post| { id: post.id, author_id: post.author_id, word_ccount: post.body.split(/\s+/).count, } end link_path { |post| Rails.application.routes.url_helpers.post_path(post) } end

Let’s start by looking at the base presenter class. Two methods, attributes and link_path, can be overwritten in subclasses to provide information about what attributes to display, and what if any HTML link to show on the object.

module FactoryBurgers

module Presenters

class Base

class << self

def presents(name)

define_method(name) { object }

end

end

attr_reader :object

def initialize(object)

@object = object

end

def type

object.class.name

end

def attributes

object.attributes.slice("id", "name")

end

def link_path

nil

end

end

end

end

And an example subclass implementation for FactoryBurgers::Presenters::UserPresenter that overrides both attributes and link_path:

class FactoryBurgers::Presenters::UserPresenter < FactoryBurgers::Presenters::Base

presents :user

def attributes

{

id: user.id,

name: user.full_name,

login: user.login,

email: user.email,

}

end

def link_path

Rails.application.routes.url_helpers.user_path(user)

end

end

The id, name, login, and email attributes are displayed on the UI. We tell FactoryBurgers to use this presenter by putting the following in an initializer file, such as /config/initializers/factory_burgers.rb:

FactoryBurgers::Presenters.present "User", with: FactoryBurgers::Presenters::UserPresenter

Notice the link icon next to the title “User”? That uses the link_path method we defined. Nice.

We also showed an anonymous presenter using FactoryBurgers::Presenters.present("Post") do ... end. How does this work? At a high level, we use the provided blocks to build an anonymous subclass of FactoryBurgers::Presenters::Base, and use that subclass identically to what we described above.

In order to do this, we’ll create a builder class. Here’s how it will be called from the present method (now would be a good time to review Ruby blocks if you’re fuzzy on them!)

def present(klass, with: nil, &blk)

presenter = with || build_presenter(klass, &blk)

@presenters[klass.to_s] = presenter

end

def build_presenter(klass, &blk)

PresenterBuilder.new(klass).build(&blk)

end

So what does the PresenterBuilder actually look like? My go-to move for metapgramming with blocks is to inherit from BasicObject and define the methods you want developers to use inside the block. Simplified here, that’s attributes and link_path. We also provide a build method. Note that we could be more strict and create a separate class for the block evaluation than the build method, for a simple DSL with fewer than five methods that was overkill.

module FactoryBurgers

class PresenterBuilder < BasicObject

def initialize(klass)

@presenter = ::Class.new(::FactoryBurgers::Presenters::Base)

@klass = klass

end

def build(&blk)

instance_eval(&blk)

return @presenter

end

def attributes(&blk)

@presenter.define_method(:attributes) do

blk.call(object)

end

end

def link_path(&blk)

@presenter.define_method(:link_path) do

blk.call(object)

end

end

# ... a few other methods including `presents` and `type` ...

end

end

If this is a little too much meta-programming for you, don’t worry about it too much. We’re building a subclass of FactoryBurgers::Presenters::Base just as we did above. We’re just doing it dynamically using code to write our new code, creating a class with Class.new and defining methods using define_method. Ruby is pretty awesome.

Headaches

Building this gem, I encountered one major headache that threatened to render the gem unusable. When you use FactoryBot, you often define sequences. For example, if you have a uniqueness validation on users.email, you might define a sequence user_email so that your first user created gets somebody1@aol.com and the next user gets somebody2@aol.com, and so on, so that your calls to create don’t blow up for violating uniqueness.

The problem is that these sequences do not persist their state across server requests. In a test suite, you don’t have to worry about server requests, and your sequences work as expected. In development, when you send one request that calls FactoryBot.create :user, then send another request from another browser click, the sequence starts from scratch and it blows up.

I came up with a quick and dirty solution, then a better but more manual solution. First, the quick and dirty:

def build(factory, traits, attributes)

resource = insistently do

FactoryBot.create(factory, *traits, attributes)

end

return resource

end

def insistently(tries = 30)

tries.times do |attempt|

return yield

rescue ActiveRecord::RecordInvalid

raise if attempt >= tries - 1

end

end

Basically, if you get a invalid record, just try again. The sequence will increment by one, and eventually you’ll get a valid record. Yeah, dirty.

There’s a craftier solution, but it’s a bit involved and so will be the subject of a separate post.

Wrapping Up (for now)

In this post, we described:

- How we want our UI to function to allow interaction with FactoryBot

- How to use FactoryBot to discover factories and traits so that we can expose this information to a UI

- A strategy to decouple our middleware and UI from the specific internals of FactoryBot

- An approach to easily customizing the display of various factories and objects using a base presenter class developer can inherit from

- Some cool Ruby metaprogramming to make defining presenters even more convenient

Stay tuned to get even deeper into FactoryBot hackery where we find ourselves holding our breath and diving into non-exposed instance variables in order to work around the sequence x uniqueness validation problem!